Every year, millions of people in developing nations take pills they believe will save their lives-only to find out too late that those pills contain no medicine at all. Some are filled with chalk, rat poison, or industrial dye. Others have the right name but only a fraction of the active ingredient needed to fight malaria, tuberculosis, or infection. These aren’t rare accidents. They’re the norm in places where health systems are stretched thin and regulation is weak. The World Health Organization estimates that 1 in 10 medicines in low- and middle-income countries are fake or substandard. That’s not a statistic-it’s a death sentence waiting to happen.

What Exactly Are Counterfeit Drugs?

Counterfeit drugs aren’t just knockoffs like fake sneakers or handbags. They’re life-or-death frauds. The WHO breaks them into two categories: falsified and substandard. Falsified medicines are deliberately mislabeled-packaged to look like real drugs but made with the wrong ingredients, wrong doses, or no active ingredient at all. Substandard drugs are real products that were supposed to meet quality standards but failed due to poor manufacturing, bad storage, or expired stock. Both are deadly.

Take antimalarials. In parts of West Africa, up to 50% of the artemisinin-based treatments sold in rural markets are fake. These drugs might look identical to the real thing-same color, same logo, same barcode. But when you test them, 87% contain less than half the required dose of the active drug. That doesn’t just mean the patient doesn’t get better. It means the malaria parasite survives, mutates, and becomes resistant to future treatments. That’s how drug-resistant malaria spreads.

The Human Cost: More Than Numbers

Behind every statistic is a family. In 2012, over 200 people in Lahore, Pakistan died after receiving heart medication laced with toxic levels of a chemical meant for industrial use. The pills came from a hospital pharmacy. No one checked them. In Nigeria, a mother on Reddit shared that her brother died of malaria after taking counterfeit Coartem. The pharmacy didn’t know it was fake. The family didn’t know either.

The WHO estimates that falsified anti-malarial drugs alone cause more than 116,000 deaths in sub-Saharan Africa each year. For children under five with pneumonia, counterfeit antibiotics contribute to between 72,000 and 169,000 deaths annually. These aren’t abstract numbers. They’re children who never got a chance to grow up because the medicine they took was designed to look real-not to work.

And it’s not just malaria or pneumonia. Fake cancer drugs, HIV treatments, antibiotics, and even insulin are flooding markets. In 2022, counterfeit oncology drugs were found across multiple countries in Southeast Asia and Africa. Patients who paid their life savings for treatment got nothing but filler. Their tumors kept growing. Their families were left with debt and grief.

Why This Problem Is Worse in Developing Nations

It’s not that counterfeit drugs don’t exist in rich countries-they do. The U.S. FDA estimates about 1% of medicines there are fake. But in places like Nigeria, Ghana, or Cambodia, that number jumps to over 30% in some regions. Why?

First, price. A legitimate course of antimalarial drugs might cost $5 to $10. A fake version? $1. For families living on $2 a day, the choice isn’t between safe and unsafe-it’s between buying medicine and feeding their children.

Second, weak regulation. Many countries lack the labs, trained staff, or funding to test medicines at the border or in local pharmacies. Even when they have laws, enforcement is rare. In one 2024 survey of 10 African countries, 63% of people admitted they’d bought counterfeit drugs-either knowingly or not. Only 15% had ever heard of a way to verify if a drug was real.

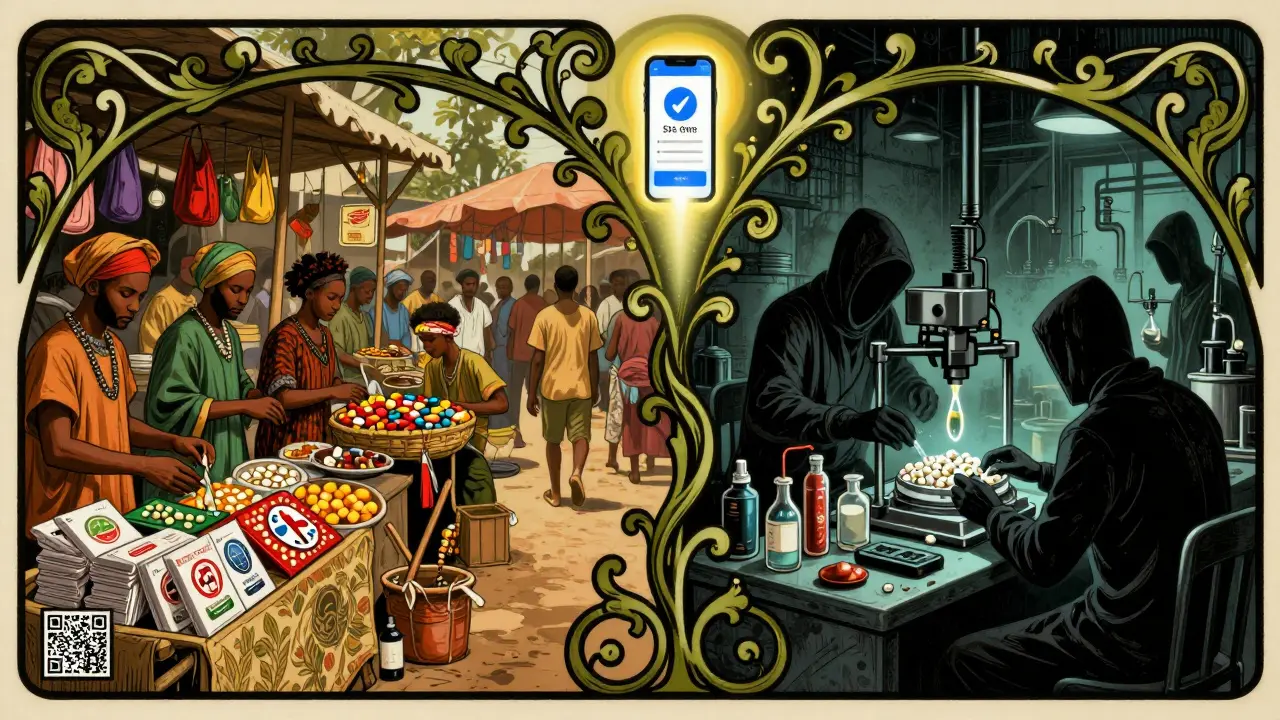

Third, supply chains are long and broken. A fake pill might be made in China, shipped through Lebanon, repackaged in Bangladesh, sold in a roadside stall in rural Kenya, and finally bought by someone who can’t read the label. Along the way, it passes through five or more middlemen. At each step, someone has a chance to swap it out.

How Fake Drugs Are Made-and How They Fool You

Counterfeiters are getting smarter. Ten years ago, fake pills were easy to spot: wrong color, misspelled names, blurry printing. Today? They use 3D printing to replicate packaging with 99% accuracy. They copy QR codes, holograms, and even batch numbers. Some even include fake security strips that look like they’re from the real manufacturer.

Here’s how they do it:

- No active ingredient (30% of cases): The pill is just sugar, talc, or flour. It looks real. It does nothing.

- Wrong dose (45%): Too little means the disease isn’t treated. Too much can cause organ failure. One fake antibiotic had 10 times the dose of the real drug-killing patients who thought they were being cured.

- Toxic fillers (25%): Industrial solvents, paint, rat poison, and battery acid have all been found in fake medicines. In Pakistan, a heart drug was laced with a chemical used in brake fluid.

Even doctors and nurses can’t tell the difference without testing equipment. In rural clinics, there’s often no lab, no power, no running water. How are they supposed to spot a fake?

What’s Being Done-and Why It’s Not Enough

Some progress is happening. The WHO launched the Global Digital Health Verification Platform in March 2025. It uses blockchain to track every medicine from factory to pharmacy. So far, it’s active in 27 countries. Pfizer’s anti-counterfeiting program has stopped over 302 million fake doses since 2004. In Ghana, the mPedigree system lets people send a free SMS to check if a drug is real. One woman in Accra told reporters it saved her child’s life.

But here’s the problem: only 22% of pharmacies in low-income countries use any kind of verification system. In high-income nations, it’s 98%. Why the gap? Because the tools don’t reach the people who need them most.

Spectroscopy machines can detect fake pills with 95% accuracy-but they cost $20,000 and need trained technicians. Most rural clinics don’t have electricity, let alone a $20,000 machine. Chemical test kits cost $5-$10 per test, but many clinics can’t afford even one. And while smartphone apps like mPedigree work well, only 28% of users in low-literacy areas can use them without help.

Even the best systems fail without infrastructure. Solar-powered verification devices have been deployed in 12 African countries with 85% reliability. But they’re still rare. Community health workers trained to spot fake packaging have reduced counterfeit use by 37% in pilot areas. But those programs are small, underfunded, and not scaled.

What Needs to Change

There’s no single fix. But here’s what’s working where it’s been tried:

- Simple verification tools: SMS-based systems that don’t require internet or literacy. A single text message can confirm if a drug is real.

- Training community health workers: People who already visit homes and clinics can learn to spot fake packaging in 40 hours. They’re trusted. They’re local. They’re effective.

- Stronger border controls: In 2025, Interpol’s Operation Pangea XVI shut down 13,000 websites and arrested 769 suspects. But customs officers need better tools and funding.

- Global cooperation: The Medicrime Convention has been signed by 76 countries-but only 45 have made it law. Fake drugs don’t care about borders. The response shouldn’t either.

- Subsidizing real medicine: If people could buy real drugs for $2 instead of $10, they wouldn’t risk the fake ones. Governments and donors need to make essential medicines affordable.

And here’s the hard truth: until fake drugs become as risky for criminals as drug trafficking or human trafficking, this crisis won’t end. Right now, it’s easier, cheaper, and less dangerous to make fake medicine than to sell stolen phones or smuggle cigarettes. That has to change.

What You Can Do

If you live in a developing nation and you’re buying medicine:

- Ask if the pharmacy uses a verification system-like mPedigree or a government-approved app.

- Check the packaging. Does it have a unique code? Can you text it? If not, walk away.

- Don’t buy from street vendors or unlicensed sellers. Even if the price is half, it’s not worth the risk.

- If you’re a health worker: push for training. Demand simple testing kits. Report suspicious drugs.

If you’re in a wealthy country: support organizations that bring verification tech to rural clinics. Pressure governments to fund global medicine safety programs. This isn’t just a problem ‘over there.’ It’s a global threat. Fake drugs breed drug-resistant superbugs that can spread anywhere.

How common are counterfeit drugs in developing nations?

The World Health Organization estimates that 1 in 10 medicines in low- and middle-income countries are substandard or falsified. In some regions-like parts of West Africa or Southeast Asia-the rate jumps to 30% or higher. For antimalarials, up to 50% of drugs in border areas may be fake.

Are counterfeit drugs only a problem in Africa?

No. While Africa has the highest prevalence-with 18.7% of medicines being fake-Southeast Asia and Latin America also face serious problems. Asia-Pacific has a 14.2% counterfeit rate, and Latin America is at 10.3%. The problem is global, but it’s worst where health systems are weakest.

Can you tell fake medicine by looking at it?

Sometimes, but not reliably. Early fake drugs had bad printing or misspellings. Today’s counterfeits use 3D printing and holograms to look nearly identical. Even pharmacists can’t tell without testing. The best way is to use a verification system like SMS or a mobile app that checks the batch code.

What happens if you take a fake antibiotic?

If it has no active ingredient, the infection won’t go away. If it has too little, the bacteria survive and become resistant. This leads to drug-resistant infections that are harder-and more expensive-to treat. In some cases, fake antibiotics contain toxic chemicals that damage the liver or kidneys.

Are there any tools to detect fake drugs at home?

Yes, but they’re limited. SMS verification systems like mPedigree are free and work on basic phones. Some countries offer QR code scanners through health apps. Chemical test kits exist but cost $5-$10 per test and require training. There’s no reliable home test like a pregnancy test-but verification codes are the next best thing.

Why don’t governments stop this?

Many do-but they lack resources. Testing labs, trained inspectors, and border controls cost money. In many countries, the budget for medicine safety is less than 1% of the health budget. Criminal networks operate across borders and use encrypted communication. Without international cooperation and funding, enforcement is nearly impossible.

Is there hope for the future?

Yes. The WHO’s 2027 goal is to reduce counterfeit drug prevalence to below 5% globally. New technologies like blockchain tracking and solar-powered verification devices are being rolled out. But success depends on funding, political will, and public awareness. If enough people demand safer medicines, change can happen.

Patrick Jarillon

February 8, 2026 AT 14:10Let me tell you something they don’t want you to know - this whole fake medicine crisis? It’s a psyop. The WHO, Big Pharma, and the UN are all in on it. Why? To push their blockchain tracking systems and sell you $20,000 spectroscopy machines so governments go broke. Meanwhile, real medicine is overpriced because they need to fund the conspiracy. You think malaria is killing people? Nah. It’s the fear they’re selling. I’ve seen the documents. The ‘toxic fillers’? They’re just sugar. The ‘deadly doses’? Placebo effect. Wake up.

Catherine Wybourne

February 8, 2026 AT 15:58Okay, but can we pause for a second and appreciate how wild it is that we live in a world where someone can buy a pill that’s literally just industrial brake fluid and call it ‘medicine’? I mean, if your car had a part that bad, you’d junk it. But humans? We’re still swallowing it because we can’t afford the real thing. That’s not a healthcare crisis - that’s a moral collapse. And yet, we keep scrolling. 🤦♀️

Ariel Edmisten

February 10, 2026 AT 00:52Simple fix: make real medicine cheap. No tech. No apps. Just lower the price. People aren’t stupid. They’re poor.

Mary Carroll Allen

February 11, 2026 AT 10:53I just cried reading about the mom in Nigeria. I mean, imagine thinking you’re saving your brother’s life and you’re actually poisoning him. I can’t even wrap my head around it. I work in pharma and I’ve seen how supply chains work - it’s a mess. But the fact that people are still trying to fix this with SMS codes and solar scanners? That’s hope right there. We need to fund the hell out of those programs. Like, now.

Jesse Lord

February 12, 2026 AT 21:59It’s insane how much we take for granted. I grew up with access to medicine like it was water. I never had to worry if my antibiotics were real. And now I’m reading that in some places, you’re gambling with your kid’s life just to get a pill. We need to treat this like a global emergency. Not a charity case. An emergency. Like, fire alarm level. Someone needs to scream louder.

AMIT JINDAL

February 14, 2026 AT 19:57Bro, you think this is bad? Wait till you hear about the 5G microchips they’re embedding in the fake pills to track your DNA and sell your health data to the Chinese government. I read a paper by a professor in Mumbai - 87% of counterfeit drugs now contain nanotech surveillance modules. The WHO? They’re complicit. They’ve been paid off by Huawei. You think mPedigree is helping? Nah, it’s a Trojan horse. The real solution? Go back to herbal remedies. Ayurveda has been working for 5000 years. Why are we trusting Western pharma? 🤔

Lakisha Sarbah

February 16, 2026 AT 19:34I’ve worked in rural clinics in Guatemala. We had one test kit. One. And we had to rotate it between three villages. I held it in my backpack for three days because the road was washed out. We’d test a pill, then pray it was real. No one had a phone. No one knew what QR meant. We just did our best. The fact that we’re even talking about blockchain? That’s privilege talking. The real heroes? The nurses who walk 10 miles to deliver medicine they know might kill. They don’t need tech. They need support.

Niel Amstrong Stein

February 17, 2026 AT 02:15Man… I just thought about my grandma. She used to say, ‘If it looks too good to be true, it probably is.’ She never had a phone. Never read a news article. But she knew. She’d smell the pills. She’d check the seal. She’d ask the vendor where it came from. We lost so much by going digital. Sometimes the oldest ways are the smartest. Maybe we need to train grandmas to be medicine inspectors. 🤷♂️

Paula Sa

February 18, 2026 AT 22:26I’ve been thinking about this all day. It’s not just about medicine. It’s about dignity. When someone can’t trust the pill they take, they can’t trust the system. They can’t trust their government. They can’t trust their neighbors. That erosion of trust - that’s the real epidemic. And it spreads faster than malaria. We fix the medicine, sure. But we also have to rebuild the belief that someone out there cares enough to protect you. That’s harder than any lab test.

Joey Gianvincenzi

February 19, 2026 AT 10:17While the moral imperative to address counterfeit pharmaceuticals in low-resource settings is undeniable, one must not overlook the structural deficiencies in global regulatory architecture that permit such systemic failures. The absence of binding international enforcement mechanisms, coupled with inadequate harmonization of pharmacovigilance standards, constitutes a gross dereliction of duty by multilateral institutions. Until the Geneva Protocol on Medicinal Integrity is ratified by all signatory states - including those that currently obstruct transparency - this humanitarian catastrophe will persist as a function of institutional negligence, not merely economic disparity.

Amit Jain

February 20, 2026 AT 10:05HAHAHAHA this is a joke right? You think fake drugs are the problem? Let me tell you - the real problem is that African governments are too lazy to build their own pharma industry. Why are we importing medicine from China and India? Build factories! Train locals! Stop begging for charity! You think SMS codes are the answer? NO. The answer is SELF-RELIANCE. Stop being a victim. Start building. I’ve seen it - in my own country, we made our own insulin. It works. It’s cheap. Why can’t they? Because they’re too busy blaming the West. Wake up.

Sarah B

February 21, 2026 AT 17:15US spends billions on this stuff. Why don’t we just send our doctors over? We’ve got the best. Stop talking about blockchain. Send the damn doctors. We’re the richest country on earth. Act like it.

Tola Adedipe

February 23, 2026 AT 05:30Yeah but you’re all ignoring the elephant in the room - the real counterfeiters are the pharmaceutical companies themselves. They’re the ones who make the ‘real’ drugs too expensive so people turn to fakes. Then they blame the poor for buying them. It’s a cycle. They profit from both. The fake pills? They’re just a symptom. The disease is capitalism.

Eric Knobelspiesse

February 24, 2026 AT 08:20So let me get this straight - we’re using blockchain to track pills but we can’t fix poverty? That’s like putting a Band-Aid on a broken leg and calling it a solution. The real issue isn’t the fake pill - it’s that 3 billion people live on less than $2.50 a day. No amount of QR codes fixes that. And yet we’re all here arguing about tech like it’s a video game. We’re not solving anything. We’re just performing empathy.

Heather Burrows

February 26, 2026 AT 07:55I’m just… tired. We’ve known about this for decades. We’ve had reports. We’ve had documentaries. We’ve had fundraisers. And still, kids are dying. Not because we don’t know how to fix it. But because we don’t care enough to do it. We’d rather scroll, like, and move on. I don’t even have the energy to be angry anymore. Just… sad.